01 Dec 2019

Author: Sumithra Urs, PhD | Sr. Scientist, Scientific Development

Date: December 2019

Skin cancers include carcinomas of all layers of the skin with the most common being basal cell (BCC) and squamous cell carcinomas (SCC). Melanoma and non-melanoma skin cancers (Merkel cell carcinoma, Kaposi sarcoma, cutaneous lymphoma and other sarcomas) are much less common. Of all the skin cancer types, melanoma is a serious form of skin cancer that begins in melanocytes, the melanin-producing neural crest-derived cells located in the bottom layer (the stratum basale) of the skin’s epidermis. While malignant BCC and SCC are rarely metastatic, the less common malignant melanoma, on the other hand, is highly aggressive and spreads rapidly to other parts of the body. Melanomas present in many different shapes, sizes and colors with a comprehensive set of warning signs.[1]

Melanoma is curable, when detected and treated early, with a 98 percent estimated five-year survival rate for U.S. patients.[2] Once melanoma becomes invasive into the skin or other parts of the body, it is more difficult to treat and can be fatal. The American Cancer Society’s estimates for melanoma in the United States for 2019 are about 192,310 new melanomas diagnosed of which 96,480 cases will be invasive, and about 7,230 people are expected to die of melanoma. The rates of melanoma have been rising rapidly over the past few decades and melanoma is one of the most common cancers in young adults (especially young women). Light skin color is a major risk factor for melanoma which is 20 times more common in whites than in African Americans, although no race is immune. The risk for each person can be affected by several factors including exposure to sun, UV light, moles, previous cancers, genetic and familial factors.

Treatment options depend on the stage of the disease, location of the tumor and overall health of the patient, and include surgical removal of the melanoma, immunotherapy, targeted therapy, chemotherapy and radiation. Frequently used single agent therapies target mutations in the B-RAF gene, the C-KIT gene and other abnormal genes. In addition, chemotherapy agents such as dacarbazine, temozolomide, nab-paclitaxel, cisplatin and carboplatin can all be utilized. Clinical trials with immunotherapy agents like IL-2, ipilimumab (CTLA-4 inhibitor), and pembrolizumab and nivolumab (PD-1 inhibitors) are underway and actively recruiting patients. These immunomodulatory drugs are also being tested in the combination setting as well as in neo-adjuvant approaches. Additionally, melanoma vaccines, BCG vaccines for stage III melanomas, and oncolytic viruses (T-VEC) are being tested.[3] New treatment options are focused on improving quality of life and increasing survival rates for patients with advanced melanoma.

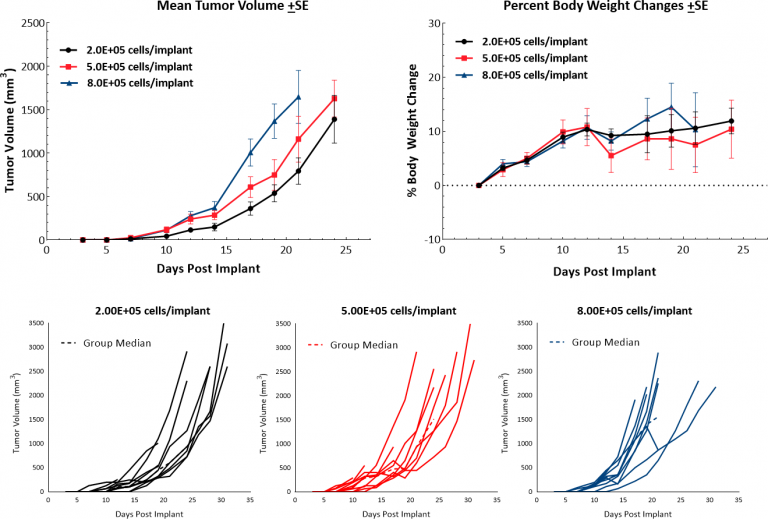

The murine B16 melanoma model is the most commonly used metastatic melanoma model for preclinical studies. We have established the syngeneic B16-F10 model to evaluate responses to immuno-oncology agents and support development of novel therapeutics. The B16-F10 cell line was generated as the 10th serial passage subclone of the B16 parent tumor line in C57BL/6 mice.[4] In vitro, these cells grow as an adherent population taking on an epithelial morphology. In vivo, intradermal implant of B16-F10 cells in C57BL/6 mice results in aggressively growing tumors. Our growth studies show efficient growth kinetics following a range of inocula with a doubling time of approximately 2-3 days (Fig. 1). Control animals stay on study for 20-25 days before they reach euthanasia criteria of excessive tumor burden. This results in a model which can facilitate up to a two-week dosing window for test agents to elicit their anti-tumor activity. While the model itself does not result in reduction of body weight, tumor scabbing, and ulcerations are common clinical symptoms associated with subcutaneous and intradermal B16-F10 tumor growth.

Fig. 1: Growth Kinetics and Body Weight Change Following Intradermal Implant of B16-F10 in C57BL/6 Mice.

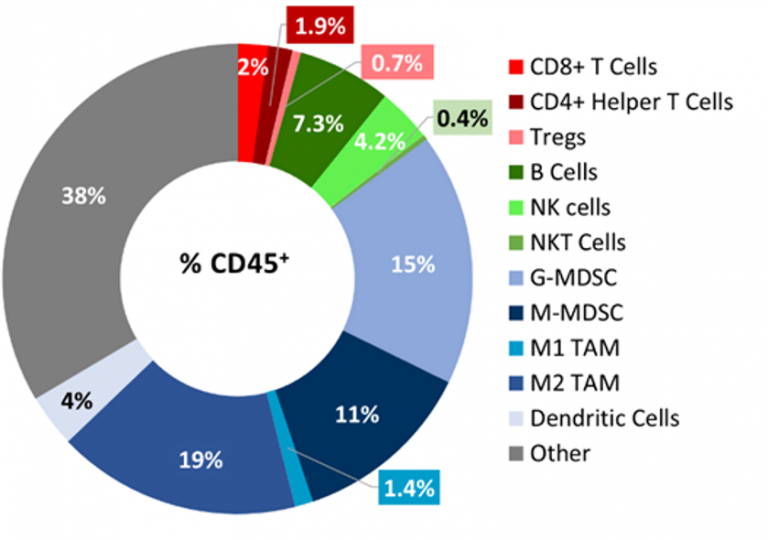

B16-F10 Tumor Immune Profile

Baseline immune profiling of B16-F10 tumor infiltrates was determined by flow cytometry on 5 untreated tumors (300-500mm3) and analyzed using the CompLeukocyteTM package. The immune cell infiltration in the tumor microenvironment, represented a percent of CD45+ cells, showed a distinct immune cell population dominated mostly by undefined CD11b+ myeloid cells characteristic to this tumor model (Fig 2). The M2 TAMs (19%), G-MDSCs (15%) and M-MDSCs (11%) were represented in relatively proportionate extents while M1 TAMs (1.4%) and dendritic cell (4%) populations were minimally represented. The lymphoid population was mostly comprised of B (7.3%) and NK (4%) cells with minimum T cell infiltration into the tumors. The overall immune profile is suggestive of a non-immunogenic model.

Fig. 2: Immunophenotyping of Tumor Immune Cell Infiltrates in the B16-F10 Model.

B16-F10 Response to Therapy

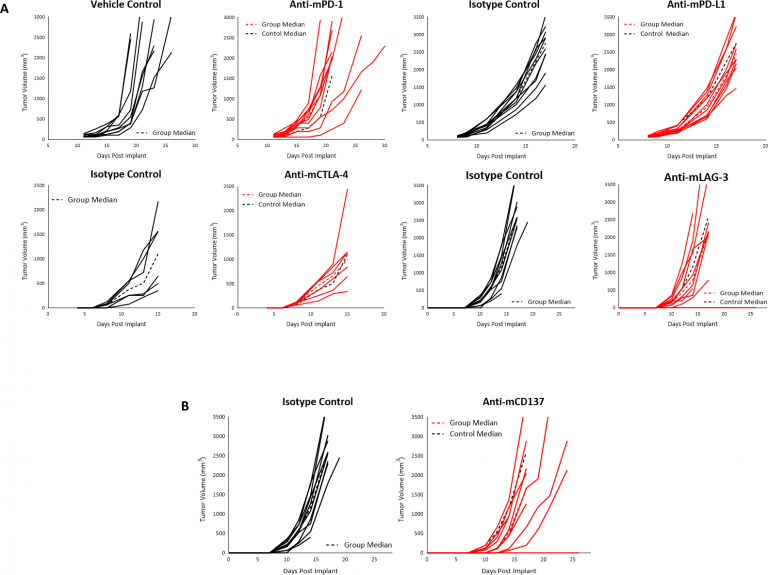

Immune Modulators:

We have investigated a number of immune modulatory antibodies in this model. Initiation of treatment when tumors reached ~90mm3 with checkpoint inhibitors anti-mPD-1 or anti-mPD-L1 did not produce any response in subcutaneous B16-F10 tumors (Fig. 3A). Similarly, initiation of treatment with anti-mCTLA-4 or anti-mLAG-3 as early as four days post implant did not produce any response (Fig. 3A). Finally, we failed to see any anti-tumor activity when B16-F10 tumors were treated with the TNF receptor family co-stimulatory receptor CD137 (Fig 3B). Given the immune-suppressive tumor microenvironment of naïve B16-F10 tumors, it is not surprising that single agent immune modulators elicit limited/no response, and this lack of response suggests an immunologically cold tumor model, as has been reported for B16-F10.

Fig. 3: Response of B16-F10 Tumors Following Treatment with Checkpoint Inhibitors (A), or Anti-mCD137 (B), in C57BL/6 Mice.

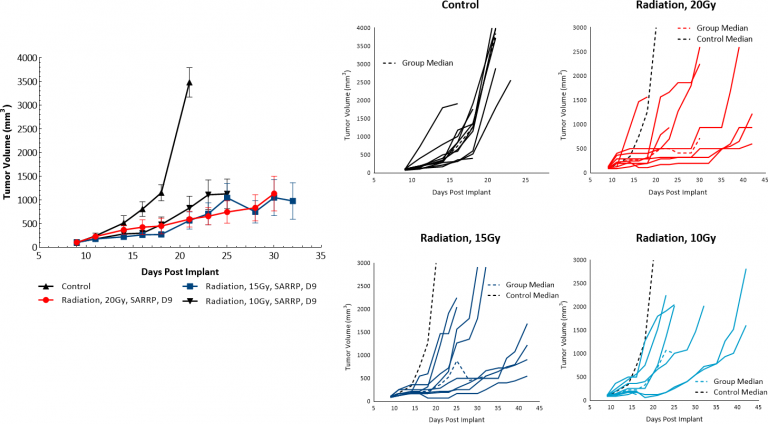

Radiation:

Radiation therapy (RT) is used in melanoma cases where patients are not good candidates for surgery or refuse surgical treatment. We evaluated the sensitivity of subcutaneous B16-F10 tumors to single dose focal radiation delivered by the Small Animal Radiation Research Platform (SARRP) from Xstrahl. Radiation treatments of either 10, 15 or 20 Gy showed anti-tumor activity in at least 50% of the animals, resulting in a dose response tumor growth delay of 5.9, 14 or 10.5 days for 10, 15 and 20 Gy RT, respectively indicating that the B16-F10 melanoma model is responsive to radiation (Fig. 4). However, even treatment at the highest dose tested did not result in significant regression or any tumor free survivors. Thus, utilization of focal RT through SARRP in the preclinical setting could be useful in evaluating combination approaches to mimic clinical development paths that include radiation treatment.

Fig. 4: Response of B16-F10 Tumors to Focal Radiation in C57BL/6 Mice.

Treatment options for melanoma patients using combination approaches with immune-modulatory agents and chemotherapy or radiation therapy are potential avenues to improve patient response.[5] In addition, combination treatment may also contribute to altering the immunologically cold nature of the tumor towards a more receptive/responsive tumor microenvironment that would become more amenable to therapy. To discuss how the B16-F10 model would be useful in your next immunotherapy study, contact the scientists.